iailat, 2024

Installazione sonora presso la Fondazione Nicola del Roscio, Roma

7 novembre 2024

Con un testo di Paola Ugolini

ITALIA-IAILAT

“L’italiano è un popolo straordinario. Mi piacerebbe tanto che fosse un popolo normale”.

(Altan)

Nel 1847, in pieno Risorgimento, il poeta e patriota genovese Goffredo Mameli dei Mannelli, morto a soli 21 anni nel 1849[1], scrive le parole del Canto degli Italiani. Questa lirica, che tutti conosciamo come Inno di Mameli, poi musicata da Michele Novaro, fu adottata circa un secolo dopo, nel 1946, come Inno provvisorio della Repubblica Italiana e ufficialmente riconosciuto per legge quale Inno nazionale solo nel 2017.

Le parole scritte dal giovane Mameli, nate in un clima di fervente sentimento patriottico, erano, oltre che colte, decisamente rivoluzionarie nell’incitamento alla ribellione contro gli invasori austriaci. Il testo è ricco di riferimenti alle icone classiche della storia della penisola italica. “Scipio” ad esempio è “Scipione l’Africano”, ovvero Publio Cornelio Scipione, generale romano che sconfisse il generale cartaginese Annibale nella battaglia di Zama, nel 202 a.C., mettendo fine alla seconda guerra punica e liberando l’Italia antica dall’esercito di Cartagine, all’epoca la maggiore potenza militare del Mediterraneo. L’Italia, dunque, si cinge metaforicamente la testa con il vecchio elmo di Scipio per ribellarsi, “destarsi” ancora una volta. “Vittoria” invece è un’invocazione alla dea, lungamente legata alla storia di Roma per disegno divino, e che ora si consacra alla nuova Italia porgendole “la chioma”, i capelli, per farseli tagliare. Mameli sta qui rappresentando metaforicamente la Vittoria che, schiava di Roma, potrà vincere la battaglia per la liberazione attraverso la recisione dei capelli. L’Inno è quindi un richiamo alle armi, all’essere pronti a morire per un ideale, e questo è ancor più esplicitamente dichiarato con le parole “stringiamoci a coorte”, un riferimento alle coorti romane esistite fino al I secolo a.C., una unità da combattimento dell’esercito composte da 600 uomini.

Il debutto dell’Inno avviene a Genova proprio nel 1847, durante la commemorazione della rivolta dei genovesi contro gli austriaci. La popolarità dei versi di Mameli crebbe poi moltissimo durante tutto il Risorgimento al punto da venire cantati anche durante le Cinque Giornate di Milano, i cinque giorni di rivoluzione armata che nel 1848 portarono alla temporanea liberazione della città dal dominio austriaco. L’Unità d’Italia, avvenuta nel 1861, viene stabilita però sotto la monarchia. L’Inno Nazionale diviene la Marcia Reale della famiglia Savoia, e bisognerà quindi aspettare la fine della Seconda Guerra Mondiale per avere un’Italia Repubblicana con un inno nazionale del popolo, “per il popolo”.

Questa breve storia dell’Inno d’Italia, che i più conoscono probabilmente grazie alla nazionale di calcio, e che talvolta abbiamo canticchiato magari sbagliando le parole, senza chiederci cosa siano Scipio e il suo elmo e la chioma della Vittoria, è per ricordarci che queste parole e il suo giovanissimo compositore incarnavano i valori di un mondo e di un periodo storico intriso di ideali di unità e di libertà per i quali poteva essere giusto, anche, morire. Rileggendo le pagine del libro di Storia, il Risorgimento italiano ci riporta all’idea dell’autodeterminazione dei popoli, non solo un impegno politico ma un’aspirazione profonda e rivoluzionaria radicata nelle singole coscienze. Ci ricorda poi, di un Italia che è oggi troppo spesso una mera espressione geografica[2], che conserva al suo interno gravi divari sociali e economici tra regioni del sud e del nord, ma anche di un paese che, nonostante vent’anni di violenta dittatura, ha il vizio di dimenticare, e non ha ancora del tutto rinnegato la prospettiva fascista dell’uomo solo al potere, come un Re taumaturgo di antica memoria. Un paese con un inno quasi spropositato per idealismo e desiderio rispetto a quanto è avvenuto e sta avvenendo oggi. E allora, cosa fare del significato originario del messaggio di Mameli? Cosa fare davanti all’oblio morale, culturale, filosofico e politico che ormai da troppo tempo attanaglia un paese che non si sconvolge quando – e lo vediamo con i recenti decreti-legge dagli evidenti intenti repressivi verso il dissenso– gli viene impedito di ‘destarsi’?[3]

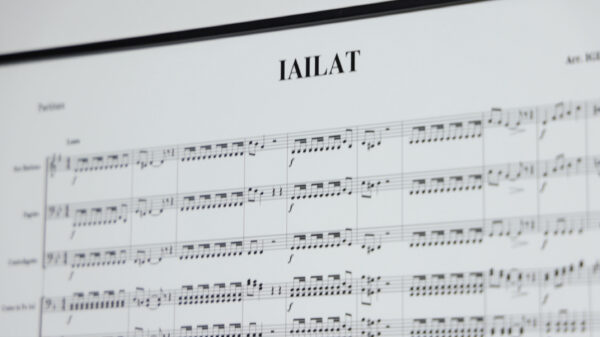

Iginio De Luca è un artista che sfugge alle definizioni disciplinari grazie alla natura poliedrica del suo lavoro, che lo fa spaziare fra vari codici linguistici come fotografia, video, performance, pittura e le sue imprescindibili e intelligenti azioni nello spazio pubblico, incursioni corsare dall’approccio situazionista. Un manipolatore della pratica artistica che sapientemente rielabora e scardina per mettere in discussione, con beffarda ironia e profondità di pensiero intellettuale, la realtà e il nostro modo di percepirla. Iginio De Luca, con Iailat (2019), performance sonora dissacrante e ludica, perfettamente in linea con le sperimentazioni della più intelligente avanguardia dello scorso Novecento, riesce a farci sentire tutto lo strazio del profondo sconforto politico che caratterizza il nostro presente di cittadini italiani. L’azione, paradossalmente banale, consiste nel far suonare l’Inno di Mameli rallentato al massimo, come se ogni nota e ogni sillaba si dilatassero fino a diventare una sorta di lamento inarticolato e straziante, ma estremamente efficace dal punto di vista semantico. L’architettura volutamente brutalista e spoglia della Fondazione Nicola del Roscio è il contenitore perfetto per far risuonare le note, stirate sino allo spasimo, dell’inno che riempiono quelle sale sotterranee, amplificando una musica trasformata in uno sgangherato e straziante lamento di dolore. Un tragicomico memento mori, il ricordo di un ideale tradito, o fallito.

Non si può restare indifferenti mentre si ascolta la beffarda storpiatura di un inno che rappresenta plasticamente la rinuncia alla libertà, come anche l’asservimento alle mafie e ai poteri fascisti, il clientelismo, il bigottismo cattolico e tutta la retorica coloniale, pro-life e antiabortista che ancora, e con rinnovato vigore, dilagano nelle piazze, ai convegni ufficiali, nelle sedi del potere. Soprattutto, rappresenta le contraddizioni di un paese che si appropria, neutralizzandoli, dei discorsi femministi, che accoglie l’omosessualità in programmi come «Uomini e donne» che nel 2017 ha ospitato i primi tronisti gay, o «Le Iene» che nel 2016, manda in onda un’“intervista doppia” a Simone e Ivan: I più̀ giovani sposi gay d’Italia, nella quale gli ideali romantici della fedeltà̀ e della reciprocità̀ hanno neutralizzato ogni possibile riferimento al carattere politico e sovversivo della sessualità omosessuale. Dunque, coppie gay sì, fintanto che siano riconducibili all’ideale della coppia e della famiglia, ma banditi tutti i movimenti queer con un’impronta politicizzata e intersezionale, che nelle piazze chiedono il disarmo, la presa di distanza dai genocidi, o che lottano per la crisi climatica. In sintesi, un paese Orwelliano dal presente ingannevole e dal futuro opaco.

Iginio De Luca è l’artista, che, attraverso la dirompenza tipica dello stile tragicomico, rompe gli schemi, rimescola il mazzo, fa saltare il tavolo e con una risata ci mette davanti alla nostra resa.

[1] – Goffredo Mameli dei Mannelli muore in seguito all’infezione di una ferita che si era procurato durante i moti per la difesa della neonata Repubblica Romana

[2] – Il 2 agosto 1847 lo statista austriaco Klemens Von Metternich scrisse, in una nota inviata al Conte Dietrichstein, la frase “L’Italia è un’espressione geografica” riferendosi alla divisione e alla reciproca indipendenza che regnavano tra i diversi stati presenti allora nella nostra penisola.

Paola Ugolini, Roma ottobre 2024

ITALY – YLATI

“Italians are an extraordinary people. I would love for them to be a normal people.”

(Altan)

In 1847, at the height of the Risorgimento, the Genoese poet and patriot Goffredo Mameli dei Mannelli—who died at just 21 years old in 1849—wrote the lyrics to the Canto degli Italiani. This poem, which we all know as Mameli’s Hymn, was later set to music by Michele Novaro and adopted nearly a century later, in 1946, as the provisional anthem of the Italian Republic. It was only officially recognized as the national anthem by law in 2017.

The words written by the young Mameli emerged in a fervent climate of patriotic sentiment. They were not only cultured but also radically revolutionary in their call to rebellion against the Austrian invaders. The text is filled with references to classical icons of the Italic peninsula’s history. “Scipio,” for example, refers to “Scipio Africanus,” or Publius Cornelius Scipio, the Roman general who defeated Carthaginian general Hannibal at the Battle of Zama in 202 BC, ending the Second Punic War and freeing ancient Italy from the Carthaginian army, then the greatest military power in the Mediterranean. Italy, then, metaphorically crowns herself with Scipio’s old helmet to rebel and “awaken” once again. “Victory” is an invocation to the goddess long associated with the divine design of Rome, who now consecrates herself to the new Italy by offering her “locks” to be cut. Here Mameli metaphorically represents Victory, enslaved by Rome, who can win the liberation battle through the symbolic cutting of her hair.

The anthem is thus a call to arms, a readiness to die for an ideal—explicitly stated in the line “Let us unite in cohorts,” a reference to the Roman cohorts of up to 600 soldiers, which existed until the 1st century BC.

The debut of the hymn occurred in Genoa in 1847 during the commemoration of the Genoese revolt against the Austrians. Mameli’s verses gained immense popularity throughout the Risorgimento, to the point where they were even sung during the Five Days of Milan, the 1848 armed revolution that temporarily freed the city from Austrian control. However, when Italy was unified in 1861, it was under a monarchy. The national anthem became the Royal March of the House of Savoy, and it wasn’t until after World War II that the Republican Italy would have a national anthem “for the people.”

This brief history of the Italian national anthem—which many know thanks to the national football team, and which we have often hummed (sometimes getting the words wrong) without questioning who Scipio is or what his helmet or Victory’s hair represent—is a reminder that these words, and their very young composer, embodied the values of a world and historical era filled with ideals of unity and freedom, for which dying was considered justifiable. When we reread the pages of our history books, the Italian Risorgimento brings us back to the idea of self-determination—not only a political commitment but a deep and revolutionary aspiration rooted in individual consciousness. It also reminds us of an Italy that, today, is too often a mere geographical expression, still plagued by serious social and economic disparities between the north and south. An Italy that, despite twenty years of violent dictatorship, has a tendency to forget—and one that has not entirely rejected the fascist vision of a single man in power, like a thaumaturgic king of ancient memory. A country with an anthem whose idealism and yearning seem almost disproportionate to what has happened—and is happening—today.

So, what are we to do with Mameli’s original message? What should we do in the face of the moral, cultural, philosophical, and political oblivion that has long engulfed a country which does not seem shocked when—through recent legislative decrees with clear repressive aims toward dissent—it is forbidden from “awakening”?

Iginio De Luca is an artist who escapes disciplinary definitions thanks to the multifaceted nature of his work, which ranges across various linguistic codes such as photography, video, performance, painting, and his essential and intelligent public-space actions—pirate incursions with a Situationist approach. He is a manipulator of artistic practice, skillfully reworking and dismantling it to question—with mocking irony and intellectual depth—reality and how we perceive it.

With Ylati (2019), a sacrilegious and playful sound performance perfectly in line with the experiments of the most intelligent avant-garde of the 20th century, Iginio De Luca makes us feel the full agony of the political disillusionment that defines our current experience as Italian citizens. The action, paradoxically simple, involves playing Mameli’s anthem slowed down to the maximum—as if each note and syllable were stretched into an inarticulate, anguished wail. It is an extremely effective act from a semantic perspective. The deliberately brutalist and bare architecture of the Fondazione Nicola del Roscio is the perfect container for these tortured, stretched notes, which fill the underground rooms and amplify music transformed into a disjointed and heartbreaking lament. A tragicomic memento mori, the memory of a betrayed—or failed—ideal.

One cannot remain indifferent while listening to the mocking distortion of an anthem that plastically represents the renunciation of freedom, the submission to mafia and fascist powers, to cronyism, Catholic bigotry, and all the colonial, pro-life, and anti-abortion rhetoric that still, and with renewed vigor, spreads through the streets, at official conferences, and in seats of power. Above all, it represents the contradictions of a country that appropriates and neutralizes feminist discourse, that welcomes homosexuality into programs like Uomini e Donne (which in 2017 hosted its first gay bachelors), or Le Iene, which in 2016 aired a “double interview” with Simone and Ivan, the youngest gay spouses in Italy. In these portrayals, the romantic ideals of fidelity and reciprocity have neutralized any reference to the political and subversive nature of homosexual identity. So yes, gay couples—so long as they fit into the ideal of the couple and the family—but queer movements with politicized and intersectional imprints are banned: movements that call for disarmament, condemn genocides, or fight for the climate crisis.

In short, an Orwellian country with a deceptive present and an opaque future.

Iginio De Luca is the artist who, through his typically tragicomic force, breaks the mold, reshuffles the deck, flips the table—and with laughter, confronts us with our surrender.

[1] – Goffredo Mameli dei Mannelli died as a result of an infection caused by a wound he sustained during the uprisings in defense of the newly formed Roman Republic.

[2] – On August 2, 1847, the Austrian statesman Klemens von Metternich wrote, in a note sent to Count Dietrichstein, the phrase “Italy is a geographical expression,” referring to the division and mutual independence that prevailed among the various states present at the time on our peninsula.

Paola Ugolini, Rome, October 2024